December 2019

To hear a sound file of the play, click here. “The Lady In White” by Brandy Stark.

Performed by Brandy Stark and Shelley Provost (the Lady).

I was selected to participate in an event called “Read No More” — a customized form of theater in which 5 authors wrote 5 different 10 minute plays. Each play contained a mystery, usually murder, and participants would move through the house to see each play.

For my play, I decided to work with the legend of the Lady in White, a ghost that allegedly haunts the Vinoy hotel. She is found on the 5th floor and is associated with water turning on in bathrooms unaided, as a figure seen moving across the floor, and with summoning the elevator, which opens to find no one there.

To write my play, I had to do a bit of research. The most likely candidate for the Lady in White, according to two local ghost books and a local ghost tour, is Elsie Elliott., the wife of Eugene Elliott.

The Vinoy Hotel:

Research started with the story of Eugene Elliott, an incredibly charismatic figure who was pivotal to the building of the Vinoy. The local legend is that Elliott was at a party with Aymer Viony Laughner and famous golfer, Walter Hagen. Hagen was hitting golf balls from the Vinoy home into the orange grove across the property. Elliott suggested that Laughner use the property to build something. Laughner allegedly met with the property’s owner who agreed to sell it only if something monumental was built. Laughner agreed and the result was the Viony.

The hotel was built in 1925 by Aymer Vinoy Laughner. Construction of the hotel took 10 months and cost $3.5 million dollars to build, which was quite a sum of money at the time. The hotel was seasonal and opened from December to March; rooms were $20.00 a night, the highest in the area at that time.

The hotel was taken over by the US Army and used for troop training during World War II. It was then sold to a private owner and continue to flourish until the late 1960s. By the 1970s, the building was in such disrepair that it was shut down. It sat empty until purchased in 1992 and refurbished for $93 million. The Vinoy’s reopening started a Renaissance in downtown St. Petersburg – one that we still enjoy today.

Eugene Elliott:

The general characteristics of Mr. Elliott include his incredible charisma, great use of language, and the ability to talk to people and keep them engaged with what he was saying.

Yet, for all that he did in St. Petersburg, Elliott is still an enigmatic figure with a mixed past. Some of the issues include the following:

Education: He claimed to have gone to 7 universities, including MIT.

Finances: Though he claimed to have money, he often did not. He projected an element of wealth in order to attract speculators.

Ethics: It was said that Eugene could sell ANYTHING, good or bad.

- When it came to selling property in Weedon Island, which he hoped to make into a Florida Riviera, he attempted to utilize the mound’s history to attract buyers. When that failed, he wanted to attract the attention of the Smithsonian Museum to build up publicity. With little response from the Smithsonian, Elliott decided to plant fake Native American artifacts in the mounds, claim that he discovered them, and send in the press to cover the story. This worked — the articles got to the Smithsonian, who recognized that the artifacts were fake but that the mounds, themselves, were quite real.

- He helped to raise $2 million dollars to build the first bridge from St. Petersburg to Tampa. This was an incredible sum of money, and when the goal was met, he told the project’s coordinator, George S. Gandy. Gandy was thrilled and told Elliott that it was time to hire construction crews, to which Elliott replied, “You’re actually going to build it?”

Since Elliott’s finances were tied to land values, he took a major hit when the Florida real estate bubble burst. On Jan. 26, 1926, IRS sent a letter notifying him that he owed $500,000 (about $5 million) in back taxes. Unable to pay it, the properties that he owned reverted to the government. On the same day, his wife filed for divorce. She wanted alimony for her and their two children (Elliott did set up a $100,000 trust for the kids).

Elliott and his wife were known for their loud arguments, indicating that there was some tension already existing in the marriage. The divorce was one of the final issues for them. They met on the back porch and had a blow out fight; she ended up dead.

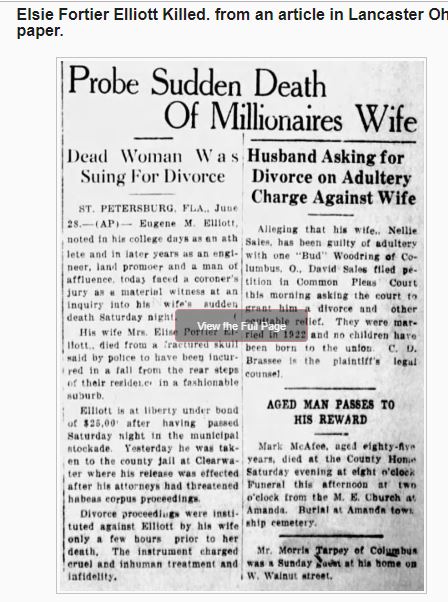

Researching the story, however, did not prove to be that easy. Discrepancies existed in the articles.

In one article, the wife who died was Eugene Elliott’s second wife, an element not mentioned in other records. Was that Elsie or someone else?

In another account, Elsie fell and Eugene carried her inside the house. He did not call a doctor, though he showed remorse at her death.

In another account, Mrs. Elliott was discovered on the ground by the family cook, Annie Judson. Elsie was injured and surrounded by a pool of blood.

The local authorities did charge Eugene Elliott for his wife’s death based upon the testimony of Annie Judson. However, the charges were dropped when the cook went missing. Speculation abounds — did she leave the country with a one-way ticket to Europe to keep her from testifying? Or did someone silence her permanently?

At least one ghost book postulates that the Lady in White may be the missing cook, still waiting for her murder to be discovered.

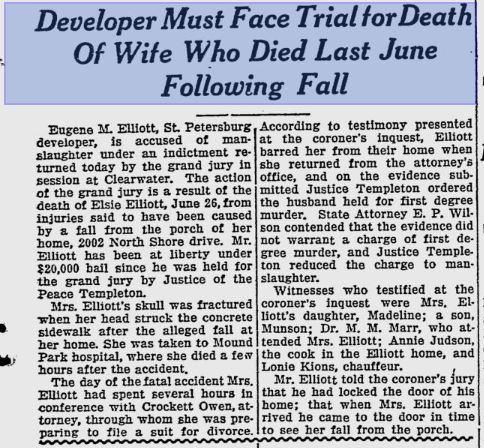

The issue? It appears that Annie Judson DID testify in court. The Evening Independent details the case and describes the witness list to include Elliott’s son, Munson, and daughter, Madeline, Dr. M.M. Marr, the doctor who attended to Mrs. Elliott, and the chauffer, Lonie Kions. Elliott paraphrased as saying that he did lock the door, but arrived in time to see Mrs. Elliott fall.

Elliott was initially brought up on charges of first degree murder, but based on witness testimony the charges were dropped to manslaughter. He was indicted of manslaughter.

Elliott sold the house in 1929 and went in and out of St. Petersburg after that. He died in 1945 of cancer in a Washington DC hospital, attended by his daughter.

The mystery of the ghostly Lady in White remains. Who is she and why is she here? Certainly, local legends have changed the facts of history to create a wonderful legendary ghost tale, but its accuracy is now in question.

However, I think that the effort resulted in a fairly decent play.

See also: https://starkimages.homestead.com/Vinoy.html

Research articles include this piece from the St. Petersburg Times, 4B, May 7, 1976.

4B ST. PETERSBURG TIMES FRIDAY, MAY 7, 1 976 O.A.T. – OF ALL THINGS DICK 00TII1UELL IT ‘An impossible human being if there ever was one. He has more knowledge, more drive, more patience, more abandon, more tact and a better understanding of human emotions and psychology than any other man I have ever known. ‘ Edward E. Naugle, Times editor, (1916-1 023), of Eugene M. Elliot He helped mold Tampa Bay area history A little breath of Florida’s zany, wild, exciting boom days of the early 20s, half-a-century ago, blew into into St. Petersburg briefly the other day. Madeleine Elliott Gardner, 66, of Miami, daughter of a major actor in the city’s mushroom expansion way back when the remarkable Eugene Elliott. A bouncy, peppery little woman with large hazel eyes and much energy, she wanted the record set right. Local historians such as Karl Gris-mer and Walter P. Fuller, she declared, hadn’t done right by her dad. Grismer, while noting that Elliott was “as clever a promoter as ever came to Florida,” referred to him as “a man of mysterious background.” SAYS FULLER: “Eugene Elliott was about the most colorful, tempestuous, super-energized man ever to grace the St. Petersburg stage.” What Mrs. Gardner objected to, among other things, is the suggestion that her father was less than sincere. As, for example, in the oft-repeated story that after Elliott put on an amazing sales campaign that sold $2-million worth of preferred Gandy Bridge stock in 122 days in 1922, he was stunned when George S. “Dad” Gandy, former Philadelphia developer and builder, said that work could soon begin on the bridge. “What! You’re not really going to BUILD, are you?” Grismer reports Elliott as gasping. “Actually,” said the promoter’s daughter, “that’s the kind of joking thing he would say he was always a practical joker.” Nor is she happy with Grismer’s remark that at many periods of Elliott’s life, he was “temporarily out of funds.” LIKE ANYONE else, he had his ups and downs. Flushed with the success of Gandy Bridge, which opened Nov. 24, 1924, Elliott plunged with grandiose “Florida Riveria,” a development of hundreds of acres centering on Weedon Isalnd mostly on paper. The Soom’s bust in 1926 put an end to that. Fuller writes that Elliott “soon faded out . . . never hit again.” “Dad and Charles R. Hall (another notable boomtime developer here) headed out to Baltimore, where they were in business, made money,” said Mrs. Gardner. “Dad put it in a trust fund now worth over $100,000 for my brother and I.” She remembered living here as a young girl, when Elliott owned a palatial home near Coffee Pot Bayou on 22nd Avenue N; a home that became the scene of a tragedy. In a family fight, Mrs. Elliott, his first wife, fell and struck her head on the edge of a concrete step, died almost instantly. “HE SOLD the house during the depression; 1929 I think,” Mrs. Gardner remembers. Mrs. Gardner and a picture of her amazing father. “The Halls and the Elliotts were the only two people in town with swimming pools . . .” An astonishing document in her possession is a 23-page article on her father, written by early-day St. Petersburg Times editor Edward E. Naugle, later in public relations. An article so effusive, so awe-struck, that Elliott emerges as a sort of Leonardo da Vinci, a master of virtually any field that attracted his keen attention. Naugle was evidently aware of this. “Many of these things I say may sound like eulogy,” he writes. “Such is not my intent or desire.” Yet for five years he was closely associated with Elliott, and is obviously sincere in his admiration. EVIDENTLY Elliott was a master salesman with great charisma. Of his speech-making, Naugle declares, “He can jam them in and keep them on the edge of their chairs, every one of them. They gladly do his bidding.” “Fuller,” said Mrs. Gardner, “says my father ‘imported’ salesmen to sell the Gandy stock. He did not. He got local people off the street and trained them. “He had people like Dale Carnegie and Napoleon Hill come and interview him, to see how he could be so successful and he used exactly the same method Hill has in his ‘Think and Grow Rich’ book. “Father had a steady, calm voice and a fantastic vocabulary; all his words were carefully chosen and he spoke in a very firm, positive way.” Elliott, marvels Naugle, was tops as an advertising man, inventor, merchandiser, sales man ager, engineer, economist. Yet he was evidently too overpowering for many, too demanding. “As might be expected,” says The Times editor, “Elliott makes few friends. He says, ‘I can’t b6 bothered.’ ” HIS LIFE STYLE, it seems, was that of the true eccentric. “He could work very hard, 72 hours at a stretch,” said his daughter. “Then when he needed a vacation, we’d go into the woods to camp; we always camped as long as I can remember. He bought a houseboat when I was little, went from Jacksonville down around the Keys and up to New Orleans and the Mississippi. “He was a good boatman, always had one. One time he rode out a hurricane, seven miles offshore from Miami.” Born in Topeka, Kansas, Dec. 18, 1872, he was determined and adventurous from the first, impatient with conformity and routine. “He always said,” his daughter recalled, “that he went to seven colleges . . . MIT was one. His parents had a huge home in Rochester, N.Y.; I think his father was in merchandising.” AFTER COLLEGE, Elliott’s father apprenticed him to a Pittsburgh steel mill. Of his four years there, the promoter later said that the experience gave him a sense of values that was life-long. Personable and suave, a sharp dresser with a quick temper, profane on occasion he quickly discovered his gift for promotion, moved around the country on a variety of jobs. “My mother,” said Mrs. Gardner, “was from Austin, Ill., a little person, quiet; they were opposites. My brother and I adored the ground that she walked on.” (Eugene Elliott Jr., a retired Army colonel, died in Miami three years ago.) “We lived in hotels all over the United States, and I really learned geography,” she said. “Later, we were in boarding school.” An ardent Republican, Elliott took a keen interest in politics. “He was in every campaign since Wilson,” she jaid. “Rode a white horse in Wilson’s inaugural parade; I’ve been bounced on Harding’s knee, had lunch with Coolidge. Father was national campaign manager for the Landon-Knox ticket.” HIS DAUGHTER is proud of many complimentary letters from governmental figures, particularly one from Franklin D. Roosevelt, which cites Elliott’s “driving energy” and adds that “I can assure you that every letter you write me is read, that the gist of it is passed on . . .” Eugene Elliott died of cancer in Washington, D.C. in 1945, nursed by his daughter. He had begun to write his memoirs, but it was too late. Truly, an amazing personality who helped mold Tampa Bay area history. r